In an earlier blog post we looked at how security operations centre (SOC) teams can shift their services up a gear, through better automation, behavioural analysis and threat hunting. The concept of threat hunting isn’t new to security operations; yet, it’s one of the most misunderstood functions a SOC team performs.

Hunting is about adopting analytical approaches and incident analysis techniques that model attacks and allow analysts to dig into what’s really going on, under the organisation’s hood.

Is your SOC ready to implement threat hunting for better risk management?

“Cyber Threat Hunting is the process of proactively and iteratively searching through networks to detect and isolate advanced threats that evade existing security solutions.”

SQRRL, A Framework for Cyber Threat Hunting

To develop a security operations service to be proactive, organisations require a mindset change, from being monitoring focused to a mode of working that is investigation led and remediation focused. This is not an easy transition for most security teams, so let’s look at why this is and explore practical steps to help.

Security Operations – it’s all about the team

Most SOC teams comprise of mainly junior operations staff, with just 10% being senior engineers, architects, team leaders, account managers and project coordinators. Junior security analysts, such as those on the SOC help desk or rostered onto the monitoring shift team, watch screens all day, every day, for alarms and work on SOC technology platforms, such as the Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system and the vulnerability management system.

A significant number of your junior analyst team are likely new to the role (within the last 12 months), since the lure of a job in cybersecurity extends to the broader workforce – so security analysts typically have experience on the general ICT service desk, network operations or in server administration. Even though the context of their job has changed to cyber security, the way the SOC analyst role operates in terms of workflow won’t have changed that much. A security analyst’s typical shift is spent looking at alarms and security information, and trying to figure out:

- How to process the vast number of alarms and warnings;

- Which alarms are real, and which are false positives;

- Whether or not to raise an incident with the customer.

The analyst’s job is largely a thankless task. Most of the alarms they respond to are false positives; which adds no value to the organisation’s security mission, meanwhile real threats slip through the cracks.

For organisations that want to become more proactive and introduce threat hunting, security operations teams need the foundation of junior analysts running SOC technology (SIEM and vulnerability management), but they also need more experienced staff, who might have a background in forensics and penetration testing.

As a SOC manager you should focus on improving automation, especially for threat verification, thus freeing up your analysts’ time to focus on hypothesis generation, investigation, discovery and threat eradication.

Your junior staff can be mentored by the threat hunting team through the first 12 months of their career to develop a more investigative outlook, thus propelling their career and focusing on the analyst role being an apprenticeship role, where future cyber security professionals learn their trade.

Overview of the Threat Hunting process

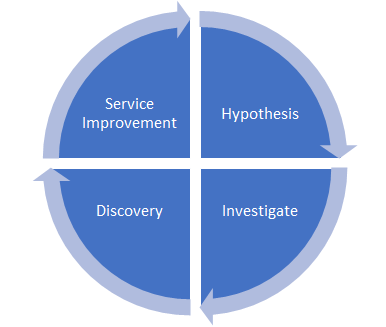

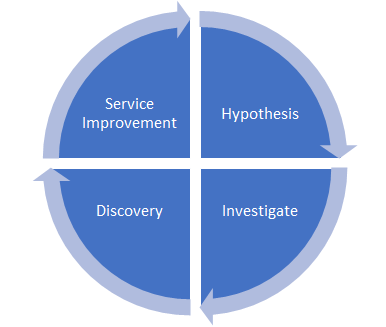

To determine the skills and capabilities needed for your new threat hunting team, you need to understand the process and how it applies to your business. Figure 1 shows a four-step process that aligns with the hunt team detecting and eradicating threats, while ensuring that the same threats don’t come back again later and cause more harm.

Figure 1 Threat Hunting Lifecycle

Hypothesis

Starting with a hypothesis, the threat hunter forms a conjecture about a possible threat that may be targeting or already attacking your business, such as a nation state actor attempting to gain access to your secret plans or customer database. To do so, the adversary may target your Internet gateway to gain remote access to your systems, from where they can dump data from your customer database.

The hunter then goes deeper beyond this high-level conjecture, developing specific hypotheses on how the adversary may launch the attack. They could, for example, start with a phishing campaign to dupe a staff member into giving up their credentials, or try blackmail against an employee to have them submit their privileged account details to the attacker, if they have a personal issue or vulnerability. So, forearmed with this hypothesis, the hunt begins.

Investigation

The threat hunter now uses each hypothesis and assesses the organisation for evidence that the methods used by the attacker have been successful. This means they look through the data (events and security information) for indicators of compromise and attack, looking for evidence that each tool or technique has been used.

The focus of this exercise is to determine which indicators of potential breaches could show threats to have been targeting or active in the environment. Investigators leverage existing analytical tools, such as the SIEM and threat intelligence solutions, while introducing additional tools for data processing and visualisation that help make sense of the noise.

Discovery

During the next phase, real evidence of an attacks can be revealed, and that evidence is used to build profiles of attacks. The hunter then maps out causality and ensures attacks cannot be repeated in a different mode, by understanding the different tools and techniques they may use to achieve the same objectives.

Building on the previous example, if the attacker is using stolen credentials, phished from a staff member using a spoofed email from the help desk, the investigator’s report can include evidence that the business’s security awareness programme is failing, while providing additional correlation rules for the SIEM (raise an alert if a user is logged on twice from different geolocations) and thresholds to monitor for excessive volumes of data leaving through the organisation’s Internet gateway. It is only through this depth of analysis that threat hunting is successful.

During the discovery phase, if the hunter finds proof of a real attack either in progress of having already happened, they would hand off at this stage to an incident manager. The investigator may remain involved in managing the incident, or they may be tasked to develop the rules and strategies to make sure this attack cannot be successful in the future.

Service Improvement

Service improvement comes in at the end of the hunting process, where a deep understanding of how an attack happens (gleaned from the previous three steps of the hunting process) is used to uplift the SOC’s capability and improve the ability to detect similar attacks in the future. The hunter provides instructions to the ICT service management team on how to tighten security controls and system auditing to make sure the SOC can detect and respond to that threat more effectively in the future.

How to build a Threat Hunting capability

You must invest in your security team’s skills and capabilities and focus on automating the regular, mundane tasks of known-threat verification, while empowering your team with a proactive remit to hunt for threats across the enterprise.

To get the most value from a SOC investment in people and analytical tools, such as a SIEM, your business should focus on building an investigation service that uses methodical, linear investigation processes to determine what could happen during an attack. Your team can then actively going on the hunt to look for evidence of this attack.

Hunting is the natural extension of the process model used by a SOC but demands a shift from a reactive to proactive culture. By undertaking this change, the rewards will almost certainly be worth the effort.

About Huntsman

About Huntsman